Insights - April 14, 2022

The Guide to Eco-Friendly Labels and Wine Certifications: Part 2 - Biodynamic

Many wine producers have certifications that decorate their bottles, here is what they represent

Written by

Aleks Zecevic

For a long time, people simply thought that wine was always natural. How can it not be, given that it comes from grapes? Others didn’t even think about it and just viewed wine as booze. However, after the Second World War, a lot has changed in the wine industry, thanks to industrial and technological advancements. Fast forward to the early 2000s, when people began paying more attention to what they eat and the origins of their food. Wine drinkers are no exception.

Today, more than ever, we see different symbols and stamps that indicate producers’ commitment to responsible farming and wine production. Often, we hear growers say that they make wine in the vineyard. And that they are either converting or have already converted their farming and entire production to green, sustainable, organic, and biodynamic methods. Some winemakers choose not to get a certification, and it is most often because of the cost and bureaucracy associated with it. Others believe that is the only way to be sure that someone is doing what they say.

The most popular certifications are organic and biodynamic, but there are also many sustainable certifications. This is the second article about certifications from the three-part series and it will focus on biodynamic certification.

Biodynamic farming is an approach that combines the principles of organic farming and concepts developed by Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher. Some of these include the use of manure and compost as a substitute for artificial chemicals; incorporating livestock into plant care; and following an astronomical planting calendar. There are nine different biodynamic preparations that help promote soil and plant health in a homeopathic way. In its purest form the farm becomes a self-sustainable ecosystem centered around capturing the energy from all elements of the farm and implanting it into all the produce that the farm grows, including grapes and finally wine.

Biodynamic teachings are approaching their 100th anniversary, but have been gaining popularity only in the last 50 years or so. The father of biodynamics, Rudolf Steiner, started his teachings on the matter back in 1924, one year before his death. Steiner didn’t drink alcohol, so his concepts were not developed for vintners. Therefore, biodynamic principles were mostly used for fruit, vegetable, and crop farmers.

Steiner was despised by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis for his suggestion that a disputed area of Upper Silesia, claimed by both Germany and Poland, should be granted provisional independence. The animosity led to the Nazis banning all his books in 1933. Consequently, all of his followers kept a very low profile, including the principles they used in biodynamic farming. Post-war industrialization and extensive use of chemicals and synthetics in farming prevented the spread of biodynamics until at least the late 1960s.

Then, in 1969, Eugène Meyer, an Alsatian vintner, was exposed to a chemical spray on his vineyard and suffered the paralysis of an optic nerve. The incident led him to read up on biodynamics, and he immediately began converting his family vineyard. From that point, on the number of winegrowers practicing continues to grow.

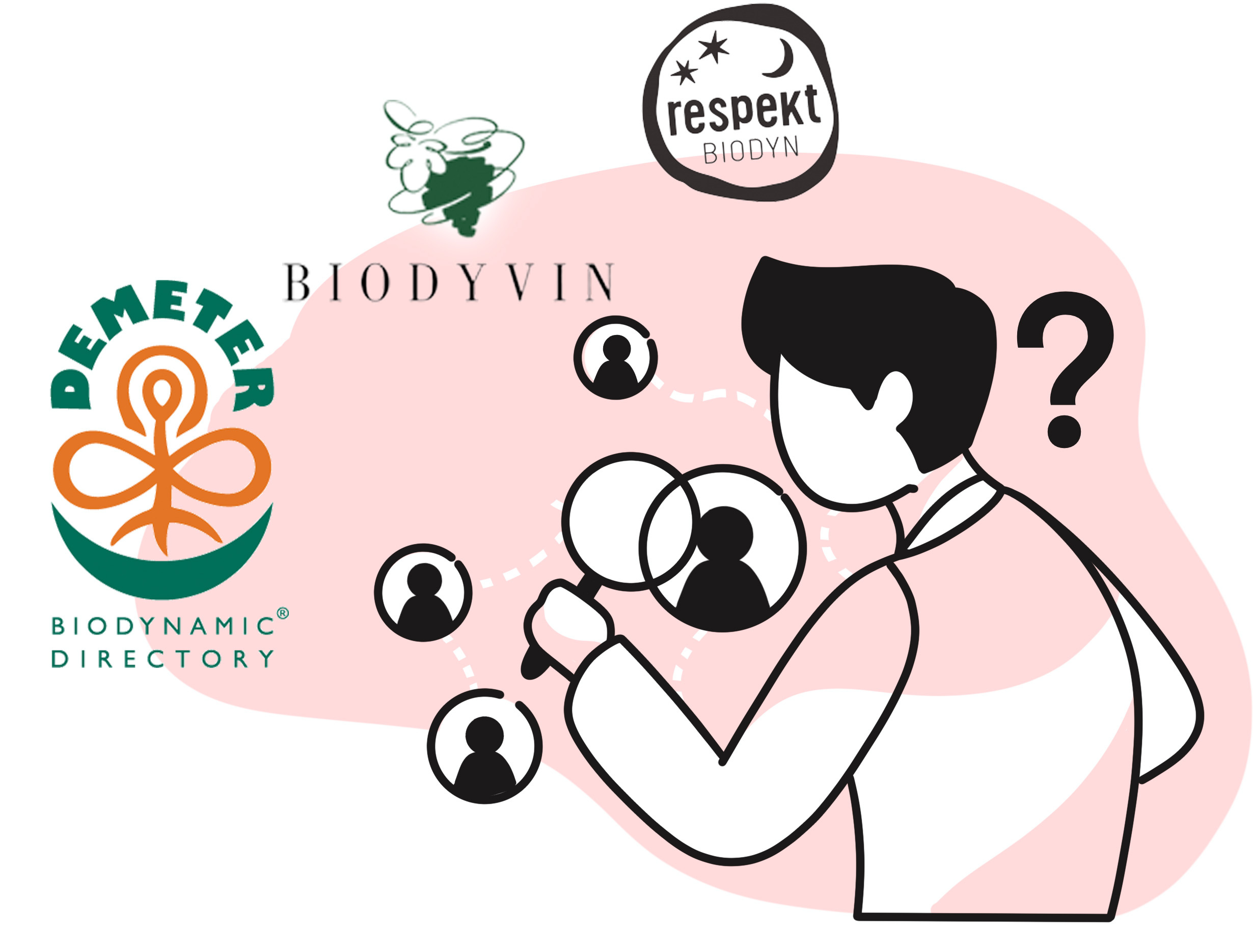

A notable difference between biodynamic and organic certifications is that biodynamic certifications are private and might have different rules among each one. On the other hand, governments oversee administration of organic certifications. Currently, the best-known biodynamic organizations are Demeter, Biodyvin, and Respekt-Biodyn.

Today, there are more than 600 Demeter-certified biodynamic winegrowers worldwide, as well as nearly 200 more that are certified by Respekt-Biodyn and Biodyvin. Of course, just like with organic farming, many winemakers practice biodynamics but choose not to get certification. Furthermore, Demeter owns the trademark terms “Biodynamic®” and “Demeter®”, which are held as certification marks providing “an assurance to consumers that the product has been certified to a uniform standard.”

Demeter is the largest certification organization for biodynamic agriculture, and it doesn’t focus only on wine. The organization has over 4,000 members, and wineries represent only 15 percent of them. Its name is a reference to Demeter, the Greek goddess of grain and fertility. The certification is used in over 65 countries currently and is difficult to come by.

Demeter farms are inspected annually for compliance with their standard in addition to the organic inspection. Demeter’s “biodynamic” certification requires biodiversity and ecosystem preservation, promoting the life of the soil, livestock integration, prohibition of genetically engineered organisms and viewing the farm as a living organism.

Demeter-certified wine must come from such farms, must be hand-harvested, must be made in a cellar that is mostly gravity-dependent with as little machinery as possible. Temperature control is permitted to steer the fermentation. The addition of sugar is a tricky topic, because although the aim is not to add it, Demeter permits adding sugar to increase alcohol by volume by up to 1.5 percent and the sugar used should be Demeter-certified or If unavailable, organic-certified. However, the concentration of the must and alcohol reduction are prohibited, but water can be added to the must. Yeast should be indigenous, but Demeter-certified or organic yeast, as well as the nutrients of the same equivalent are also permitted.

Bentonite clay and organic or biodynamic egg whites or milk are also permitted during processing, as well as the addition of sulfur dioxide. Sulfur has different rules depending on residual sugar and color of the wine. Hence, wines that have less than 5 grams of residual sugar can have up to 140 and 110 parts per million of total sulfur for whites and reds respectively. Wines that have over 5 grams of residual sugar, can have up to 180 and 140 parts per million for whites and reds respectively. Sparkling wines have the same rules as white wines, while sweet wines can have up to 360 parts per million of sulfur dioxide in total.

"Biodynamic Labels"

Respekt-Biodyn and Biodyvin have similar, but more wine-centric rules. The main similarity is that unlike Demeter, both organizations focus on winegrowing only. Hence the taste and profile of the wines are also important. Respekt is the smallest biodynamic organization with its headquarters in Austria. Their members are mainly in Austria but also in Germany and Italy (and one of the Austrian members has vineyards in Hungary as well). They currently have 29 members and are open to receiving more. Most importantly, Respekt sees itself as more than just a certifying body, but rather as a group that promotes the exchange of ideas and experiences and encourages collaboration between members. As a matter of fact, Respekt relies on independent inspection organizations, like Lacon, Abcert and BioControl.

Biodyvin was created in 1995 and is a group of 192 winegrowers in France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Switzerland and Spain. Together with EcoCert, they execute inspections of estates that are members, or in the process of becoming members. Only properties farmed entirely biodynamically, or those that have committed to full conversion after three years, are accepted. Total sulfur permitted is slightly lower than according to Demeter’s standards, with the lowest being 80 parts per million for red wines that are matured for less than nine months. The biggest difference, though, is for sweet wines, where Biodyvin permits only up to 230 parts per million.

Taking all the rules of these certifying bodies into consideration, many wine professionals will agree that there are winemakers out there who are not certified but go beyond what is allowed in both organic or biodynamic production, often being more rigorous, using way less sulfur dioxide and restricting the use of other aids. Most often, these are the wines that differ in taste from conventional wines. One of the many misconceptions is that certified wines will taste much different, but unfortunately, that is not always the case.

Our latest stories and podcasts:

PODCAST EPISODE

Theresa Olkus of the VDP

Aleks Zecevic interviews Theresa Olkus, the managing director of the VDP

PODCAST EPISODE

Austrian Wine with Chris Yorke

Aleks Zecevic interviews Chris Yorke, CEO of Austrian Wine

PODCAST EPISODE

Treading the Grapes with Simon Woolf

In this episode, Aleks Zecevic interviews the Amsterdam-based wine writer, Simon Woolf