Insights - April 8, 2022

The Story of Romorantin

The renaissance grape is producing high quality wines, but it flies under the radar

Written by

Aleks Zecevic

There are more than 10,000 identified wine grape varieties in the world, but a very small percentage of them has achieved global fame and praise, and for good reason. However, there are many grapes out there that deserve the popularity but are grown in such minuscule amounts that only true wine geeks get to truly experience them. One of these grapes is Romorantin, a unicorn variety, mostly because of the size of its plantings, but also for its wine insider profile.

Romorantin, or Romo as its growers call it, is a light-skinned variety grown almost exclusively in the east of the Loire Valley. Although it is classified and permitted throughout the region, it only grows on 80 hectares (200 acres) in Loir-et-Cher. Surprisingly though, it has its own appellation - Cour-Cheverny, which was promoted to an Appellation Origine Controlée in 1993 and where Romorantin is the only permitted variety. It is not cultivated anywhere else with real significance, neither in France nor in the rest of the world.

“It is very interesting to have the opportunity to grow and taste a very old and rare grape, from the Renaissance that exists only in Cour-Cheverny,” says Vincent Chevrier, the owner of the biodynamic winery, Domaine de Montcy, and an active spokesperson for the variety.

"Courtesy of Domaine de Montcy - Vincent Chevrier"

There are many synonyms for the grape, but the most common ones are Framboise and Dannery. Along with Romorantin, the three names appear successively in the 18th and 19th centuries and are used locally in Orléanais, Bourbonnais and Loir-et-Cher. Its current name is most likely due to its connection to a town in the area called Romorantin-Lanthenay, commonly referred to as Romorantin.

Framboise might be the most interesting name for the variety. “This word was used to describe a wine that has a good ‘framboise’, meaning nice fruit and quality,” explains Chevrier. It marked wines of distinctive quality with an identifiable taste to the wine. Basically, it meant a cultivar with grapes likely to produce a wine with a marked taste or scent, as opposed to other "flat" wines. The word has since disappeared from the technical vocabulary.

The origin of Romorantin is a bit of an enigma. It is hard to figure out the date of the grape crossings, even with DNA profiling. Therefore, we can only trust what we find in literature, but that can also be deceiving. The first mention of Romo was in 1868 in Pierre Rézeau’s Le Dictionnaire des Noms de Cépages de France (Dictionary of Grape Variety Names of France).

However, it is widely believed that Romo was brought to the Loire by King Francis I (François 1er) back in 1518. The king had a residence in the town of Romorantin, and it is documented that he brought in some 80,000 vines from Burgundy designated as “complants de Beaune” or plants of Beaune, which was back then a widespread synonym for Pinot Noir. Allegedly, this was in fact Romorantin. This is very possible, because DNA fingerprinting at UC Davis concluded that Romorantin is one of 16 grapes that resulted out of a cross between Gouais Blanc (Heunisch) and Pinot Fin Teinturier (sub-variety of Pinot Noir). This means that it is a sibling of varieties such as Chardonnay and Aligoté, which are prominently grown in Burgundy.

It is also possible that the variety was obtained in Orleans, which is much closer to where the grape is cultivated nowadays, especially since at that time, the Orleans vineyard included Sologne which is within the confines of Cour-Cheverny today. “We don’t know where the crossing happened, but the first mention of what we think is Romorantin, was in Orleans in 1710 under the name Framboise,” says Chevrier.

The cultivation of this grape variety is attested in this area by Dr. Jules Guyot in 1868. The Ampelography of Viala and Vermorel estimated its effective introduction in the department in the 1830s and allegedly was brought there by an unknown grower. From here, the variety moved to the Loire

This area has been important for winegrowing since the Middle Ages. Centered around the site of the current Château de Cheverny, the royal vineyards here witnessed significant growth during the Renaissance period mainly because of the location, since the Loire was a commercial axis. Moreover, in 1577 the famous edict promulgated by the Parliament of Paris prohibited residents from “buying wines produced less than 20 leagues (55 miles) from the capital.” This law significantly improved the development of such aristocratic areas.

However, with the phylloxera crisis that started in 1876 and the newly built railway, which allowed for smoother transit of wines from the south of France, affected the Loire. Its vineyards fell out of favor during this time and after the crisis was over, the plantings were reconsidered and grapes like Chenin Blanc, Pinot Noir and Sauvignon Blanc were selected to replace most of the region’s varieties.

Still in the late 1950s there was 680 hectares (1680 acres) of Romorantin. Since then, the grape’s plantings drastically declined to an eight of that. The plantings today are almost entirely limited to the Cour-Cheverny AOC, which overlaps with the larger appellation of Cheverny AOC, which produces wines of more popular grapes – Pinot Noir and Gamay for reds and rosés, and Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay for the whites. Considering the commercial success of these grapes, but also the friendlier nature of the wines, growers in the area started neglecting Romo, which at that time presented the idiosyncratic side of wine, with its high acidity, proneness to oxidation and rough tannic structure.

Despite this old reputation, with climate change and improvements in viticulture and winemaking, the quality of Romorantin has reached new levels. The variety is quite fertile and productive, so yield management and the age of the vines is very important. “You need old root system, because in the first several years, the wines are more simple,” says Alexandre Gendrier, owner and winemaker at a biodynamic wine estate, Domaine des Huards.

"Courtesy of Domaine des Huards - Alex Gendrier"

It can be pruned long or short. However, the key to success is planting it in soils that promote early-ripening. This is because Romo has thin skins, which means it is sensitive to diseases and rot, especially botrytis. The goal is to achieve phenolic ripeness without too much sugar. The grape is naturally high in acidity, and because of its low flesh-to-seed ratio, Romorantin wines are often characterized by tannins. Hence, if the pit is ripe, the tannins will be as well, leading to a less astringent profile.

The delicate nature of the Romorantin vines can also be one of the reasons for its scarcity. “Romorantin is very fragile, for example when the shoots start to grow, you have to be very careful, if the wind is strong, you can lose a lot [the crop],” explains Gendrier. “Also the growing cycle for Romorantin lasts longer than [than other grapes we grow] and the longer it’s outside, the higher is the risk, you know!?”

“The skins of Romorantin are thinner and its leaves are larger, so it is pretty sensitive to botrytis,” explains Simon Tessier of Domaine Philippe Tessier. “But it is less sensitive to mildew,” he points out. Chevrier, on the other hand believes that Romo is well suited for climate change because of its acidity, but also natural resilience.

Additionally, with proper management, oxidation can be prevented. “What gets oxidized first, doesn’t get oxidized after,” says Gendrier, explaining that he would introduce oxygen to the newly pressed juice, which creates a sort of immunization against oxidation.

Most Romorantin is planted in limestone soils, but there are some versions that hail from sandy soils, as well. With limestone, wines tend to be lower in pH and higher in acidity. This makes the wines less approachable in their youth, taut. Producers who grow it on limestone often wait several years to release their wines for this reason. On the other hand, when grown in sandy soils, the pH goes up and acidity goes down. Romo from sand is more approachable, luscious, and broad, with riper flavors and less acidity. Similarly, malolactic fermentation can have a strong impact for the taste of Romorantin, transforming it from being sharp and precise white to broad and round.

Simon Tessier also produces a version that is skin-fermented in qvevri for over 6 months. “I am pretty happy with the results, but need to keep it for 3 years before releasing it,” he says. This cuvée is called Romorantique.

"Courtesy of Domaine Philippe Tessier - Romorantique"

"Courtesy of Domaine Philippe Tessier - Qvevri"

Most commonly, Romorantin wines are characterized with aromas of honeysuckle or acacia, as well as citrus fruits. Depending on harvest and maturity, beeswax or honey and a hint of prunes can evolve. Most importantly, Romorantin produces tannic white wines, of unique texture. In blind tastings it is often confused with Savagnin from Jura, or Chenin Blanc from Anjou.

“I have some clients who compare it to Savagnin, and [I think] this is for two reasons: the tannic structure, but also the oxidative nature of the two grapes,” explains Simon Tessier.

Romo finds its best pairings with seafood, especially fattier fish, or noble shellfish such as scallops. However, it is very versatile, and it can pair very well with poultry, game birds and even pork. It is also great with many dishes from Asian cuisines, especially sushi, but also curries and non-spicy foods with soy sauce. Finally, it can stand up too many types of cheese.

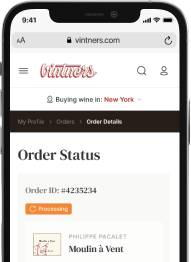

The fading popularity of Romorantin could mean it ultimately cease to exist. However, there are tenacious growers who believe in Romo’s revival. Below is a list of 6 vintners whose Romorantin wines would impress even the most critical tasters.

Recommended producers (in alphabetical order):

François Cazin of Le Petit Chambord – Cazin practices sustainable farming and all his vineyards are hand harvested. He makes two Romorantin wines, both that grow on limestone, within the Cour-Cheverny AOC, both are spontaneously fermented in stainless steel and both don’t go through malolactic fermentation. The first one is a straight Cour-Cheverny white, with the signature grip and vivacity of the variety. The other is called ‘Cour-Cheverny Cuvée Renaissance’ and it is made only in vintages when the weather conditions allow for a late harvest of healthy fruit. This wine is made exclusively from old vines (40 – 90 years) and it is always bottled with some residual sugar (between 20-30 g/L). Although on the sweeter side, the natural acidity creates a lovely balance.

Claude and Etienne Courtois of Les Cailloux du Paradis – Claude is Etienne’s father and has founded the winery, but Etienne is in charge today. This biodynamic property is located in Sologne and they make one Romorantin (labeled simply as ‘Romorantin’) from fairly young vines that grow on limestone. The wine goes through malolactic fermentation, is aged for 40 months in barrels before release and bottled without addition of sulfur. This Romorantin is idiosyncratic, but shows great complexity.

Julien Courtois – Julien is the son of Claude Courtois and Etienne’s brother. He created his own vineyard, Le Clos de la Bruyère, in 1998 in Soings en Sologne following similar principles to farming and winemaking (biodynamic and shying away from sulfur usage). He makes one Romorantin cuvée called ‘Autochtone’, from grapes that grow on limestone soils. The wine is aged for 18 months in large foudre, it goes through malolactic fermentation and is bottled without addition of sulfur. The wine is also distinctive expressing a mix of fruit and savory notes.

Domaine des Huards – A biodynamic estate in hands of the Gendrier family, which dates back to 1846. They have been producing wines from Romorantin since 1922, and still have these 100-year-old vines. Today, Alexandre Gendrier is taking over the reins from his father Michel. They make three different wines from Romorantin: Romo, François 1er and JM Tendresse. All three are labeled under the Cour-Cheverny AOC and don’t go through malolactic fermentation. Romo is the intro to the grape, François 1er is their higher end version made from oldest vines at the estate (75 years on average) and JM Tendresse is their off-dry version perfect for foie gras, ripe cheeses, but also as an aperitif.

Domaine de Montcy – A biodynamic estate owned by the Chevrier family with Vincent Hayer as the head winemaker and managing partner. The domaine grows 4 hectares (10 acres) of Romorantin and produces two different wines in the Cour-Cheverny AOC: Luce and Licorne. Both hail from limestone soils and don’t go through malolactic fermentation, but the main difference is that Luce is aged in stainless steel, while Licorne is aged in oak.

Domaine Philippe Tessier – Domaine Tessier was founded in 1961 by Roger Tessier, with his son Philippe taking the reins 20 years later in 1981. Today, Philippe’s son, Simon is taking over the reins. The domaine has made 6 different cuvées from Romorantin over the years, all that undergo malolactic fermentation, under the Cour-Cheverny AOC. The most important differences are that some cuvées come from limestone soils, while ‘Les Sables’ comes from sandy soils. Lastly, there is the Romorantique, which, as previously mentioned, is a skin-contact version, spontaneously fermented in qvevri, macerated for 7 months.

Our latest stories and podcasts:

PODCAST EPISODE

Theresa Olkus of the VDP

Aleks Zecevic interviews Theresa Olkus, the managing director of the VDP

PODCAST EPISODE

Austrian Wine with Chris Yorke

Aleks Zecevic interviews Chris Yorke, CEO of Austrian Wine

PODCAST EPISODE

Treading the Grapes with Simon Woolf

In this episode, Aleks Zecevic interviews the Amsterdam-based wine writer, Simon Woolf